HELIOPHILIA VS. UMBRELLIZATION

Cosmic Imperialisms in Los Angeles

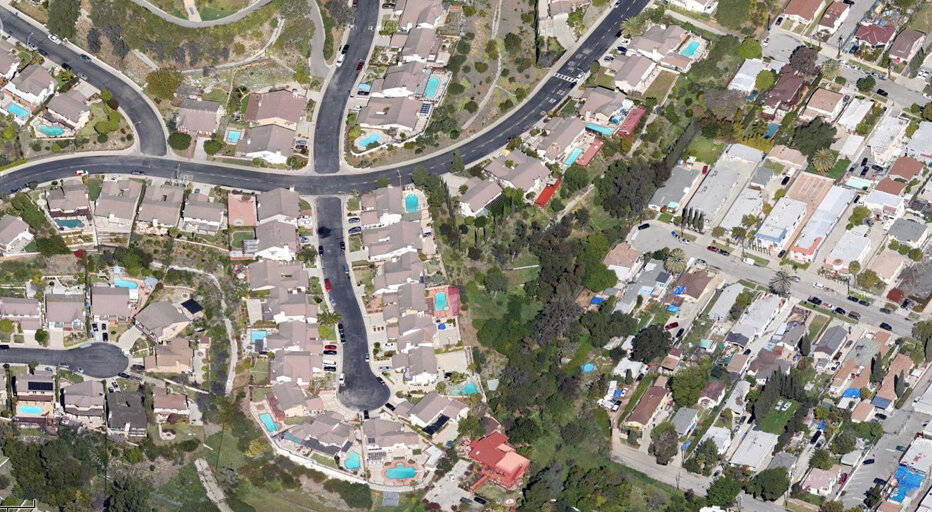

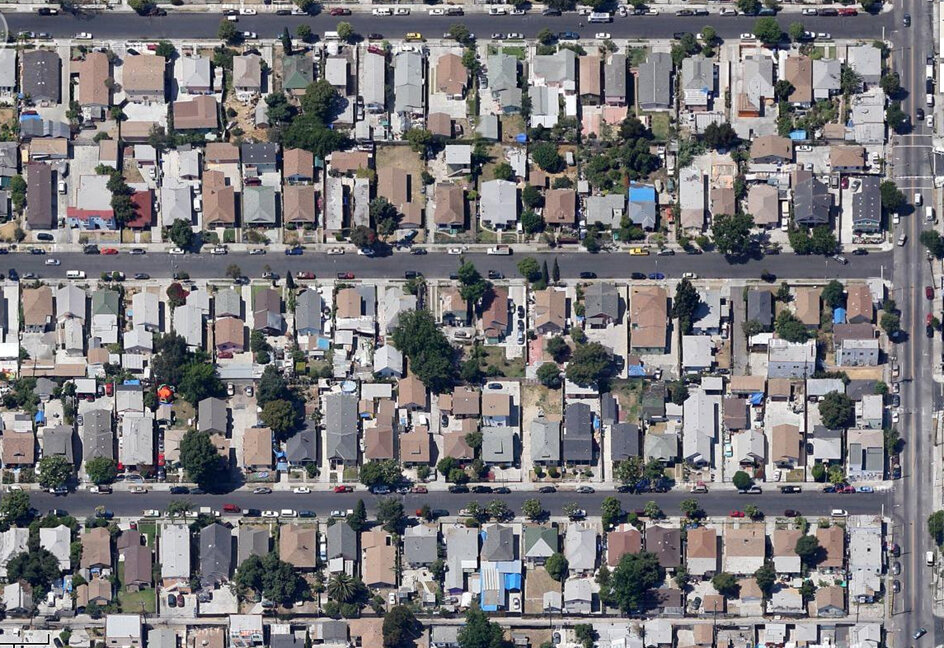

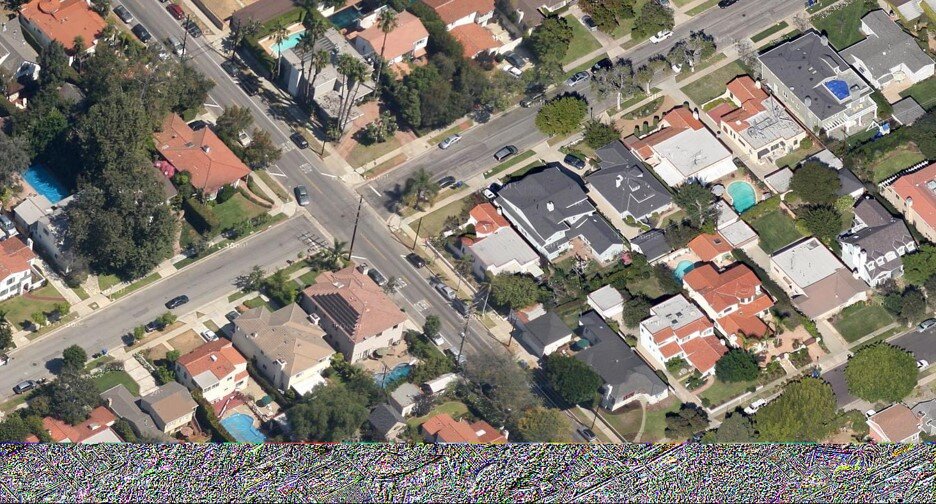

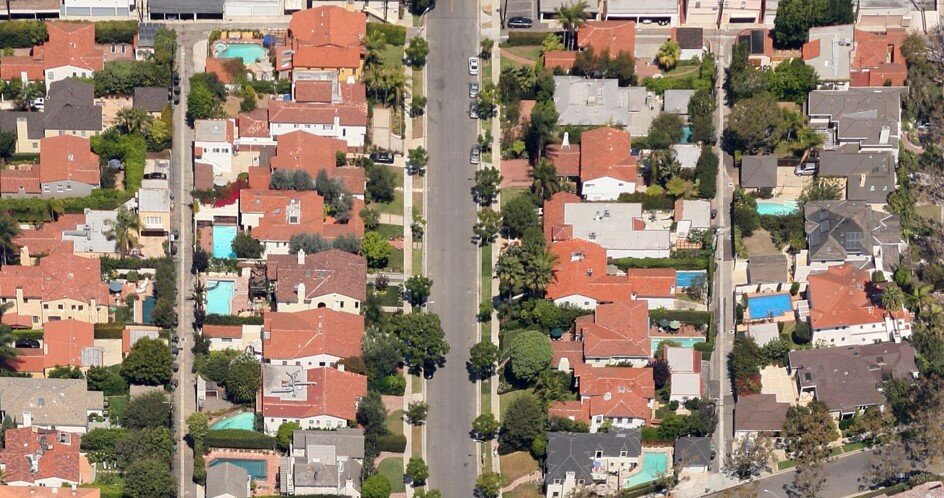

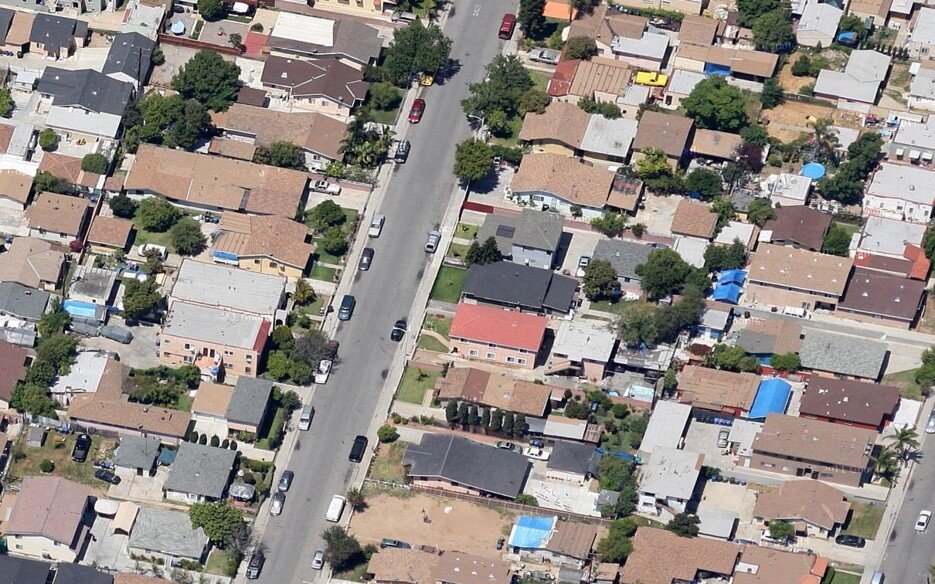

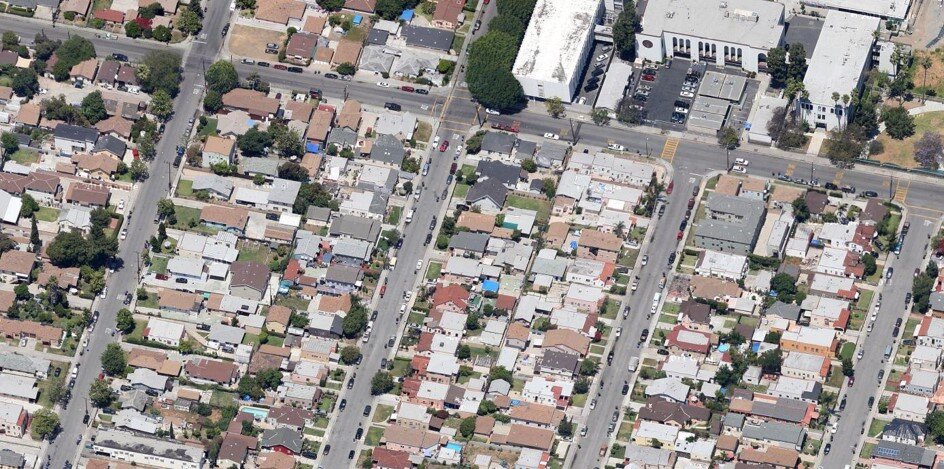

The information on this page is from a presentation I gave at the Velaslavasay Panorama Museum in Los Angeles in 2012. During that year I was involved with Hillary Mushkin's art-geography research group called Incendiary Traces, the goal of which is to explore the political act of representing the Southern California landscape. The talk I gave was called "Heliophilia Vs. Umbrellization," a title that suggests each of the two reasons that one would see blue specks covering the L.A. landscape when seen from above. Blue specks in Southern California come in the form of swimming pools and in the form of tarps. The former predominate the western half of the metropolis, where movie stars reside along with wealthy elite, while the latter tend to cover the eastern half of the city, a region in which nearly 75% of people speak Spanish as a first language.

In a wonderful discovery, fellow "Tracer" and program manager at the Center for Land Use Interpretation, Aurora Tang, sent me information about two artists who published The Big Atlas of LA Pools. It's nice to know that there is an international cadre of at least three people who have studied Los Angeles swimming pools from above.

Here is a slideshow of the images I used in the talk:

Here is the text of the talk:

This presentation is a young thought experiment for me: some of it will add up, and some of it likely won’t. At the very least I hope it offers a framework for how we might organize thinking about the ways in which Angelenos have formed relationships with the natural world with respect to Western imperialist traditions. While this afternoon we are hearing about the role of palm trees in the practice of ecological and botanical imperialism, I want to tell two brief stories about a more cosmic piece of nature – specifically, the sun. Using a set of Google satellit screen shots, I read the history of two responses, or adaptations, to living in the temperate climate that is Los Angeles. To me these two responses represent different ways of dealing with, or controlling the elements of light, radiation, and heat. When remote-sensed through aerial photography, these adaptations bear a striking similarity: the light blue specks of water seen in upper-middle class residential swimming pools, and their more inland counterparts, the blue plastic tarp awnings set up throughout residential neighborhoods east and south of downtown. Bringing palm trees to the southland is a form of colonizing the landscape via an importation of botanical specimens. And while not as deleterious to the ecosystem as other instances might be, the palm still invades our perception of what our city should look like. Importing the palm to L.A. is either an aesthetic metaphor for colonization, or a material, historical extension of European colonization, or both. Likewise, one might interpret the visual prominence of bluish specks throughout the city as representative of different cosmic imperialisms.

The ubiquity of swimming pools in parts of the city is part and parcel of the century-long, Herculean effort to – and this may be a leap – deny L.A. for what it is: a temperate region. There is an artificial normalization of weather on days that are “perfect” – 75 and sunny. It is almost as if heat, rain, and cold are considered imperfect, as if they were not part of what defines a temperate climate. I see this as city-wide, even nation-wide popular belief that L.A.’s climate is not actually temperate, but closer to desert, or at least a cool day in the desert. This belief refuses to see the sun as a Mediterranean sun. Instead, belief about what defines a normal, or perfect weather day sees the sun as a desert sun, but with continental rainfall, a seemingly impossible contradiction made possible by importing the water resources to fill the pools. So, while on the one hand swimming pools may be seen as a rejection of climate, they are on the other hand a worship of the sun.

There is of course a geography to this heliophilia. An extremely unscientific study shows that pool cleaning services are located where one might expect – west L.A. and Beverly Hills, and are virtually non-existent in other parts of the city where umbrellization has won the day. The extent of sun worship in Los Angeles is even more intense that one might imagine, though, as can be seen from cartographic glimpses of the locations of tanning salons. Are customers at tanning salons the same people who own pools? I for one love the sun too – I admit to swimming outdoors as often as I can. This relationship with the sun is, however, an extremism. Flocking to L.A. precisely because of the sun has a deep history in health boosterism dating to the mid-19th century. With the ability to cleanse the airs, soils, and waters, and therefore the body, the southern California sun has for Anglo migrants always held a position of power in their imagined version of what an uplifting, healthy landscape should be. By constructing swimming pools by the thousands, Angelenos open full face to the sun, exposing the body to the heat of the cosmos, while masking its immediate discomforts with imported water.

Whether or not this vision of a therapeutic sun is borrowed from previous Anglo colonial encounters is, for now, up to the panel and the audience to decide. If it is, though, we might interpret the swimming pool as a geographical reinscription of – as Hillary put it – a “mythic version of Western empire’s sub-tropical reaches.”

The blue plastic tarp awnings that dot the eastern and southern regions of the city represent – like the swimming pools – a cultural response to living in the subtropical sun. But one could make the case that the relationship with the sun as manifested in tarp awnings is practically the opposite of the swimming pool. That is, they reject rather than celebrate the heat and radiation of the sun. Or, if want to look for similarities between them, it could be that each is an escape from the sun, with the water tempering the heat just as the shade of the awning does.

If we see my interpretation of blue specks across the city as a story about access to nature, then the blue tarp awnings offer a completely different version of the sun. In this version of what the sun should mean, water, heat, radiation, and light are reduced by the blocking agency of the tarp. It is a different way of being outdoors, which, like the pools, retains its sense of privateness and leisure, but does so without worshiping the solar subtropical blaze. It seems, in many ways, more of an acceptance of the climate for what it is, without attempting to mix & match characteristics of different climate zones (i.e. temperate and continental). Blue tarp awnings are often set up over gated driveways, converting the concrete parking area into a covered year-round porch. Is this a reflection of lack of public space in the city? An extension of the living room on certain days of the year? If so, this is not so unlike the function of private swimming pools.

I’ve identified two variables that seem to correlate with blocking the sun’s heat, radiation, and light with plastic tarps. One is the ubiquity of the near shade-less palm trees. It is not too far of a stretch to think that in a landscape dotted with, say, native live oaks rather than palms, there would be less of a need to create protection from the sun. This harkens to the notion of re-making nature over and over again, something that has become commonplace in southern California, and why, as an urban-environmental geographer, I am so continuously enthralled with this city. Geographers speak of “second nature” to describe how people have altered environments, but in L.A. it’s not inconceivable that we should be talking about third and fourth natures. To replace native shade-giving flora with decorative ornaments of imperialism, then to replace the function of those lost trees with blue plastic tarp awnings is – to me at least – nothing short of captivating.The second variable that seems to correlate with the use of tarp awnings to block the sun is building density. This is by all means related with the question of access to public park space.

Conclusion

The visual similarity of the pools and the awnings both showcase moments of adaptation to living in a subtropical climate. But despite their visual congruence in aerial photos, their presence in the landscape could bely distinct imperial visions of southern California, and distinct relationships with the natural world vis-à-vis the sun. My initial impulse in this project was to look for differences between Anglo and Iberian colonial imaginaries to see if there might be historical precedents for heliophilia and umbrellization, respectively. As of now I have not explicitly researched this at all. The possibility for such precedent, though, is certainly there. I will leave the panel and the audience with two questions: are these adaptations to living in the sun relics of imperialist practices in the same places where the very idea of exotic-ness was born? Are swimming pools and plastic tarp awnings – aside from their visual similarity – two sides of the same coin of controlling nature?