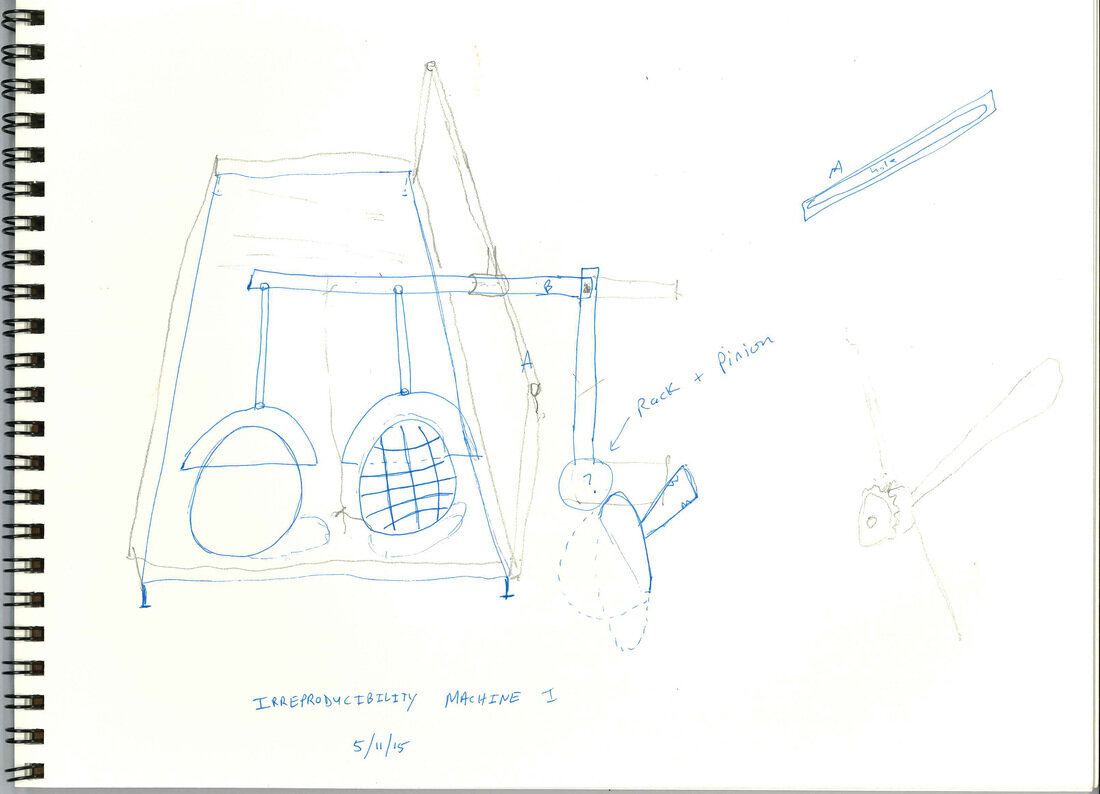

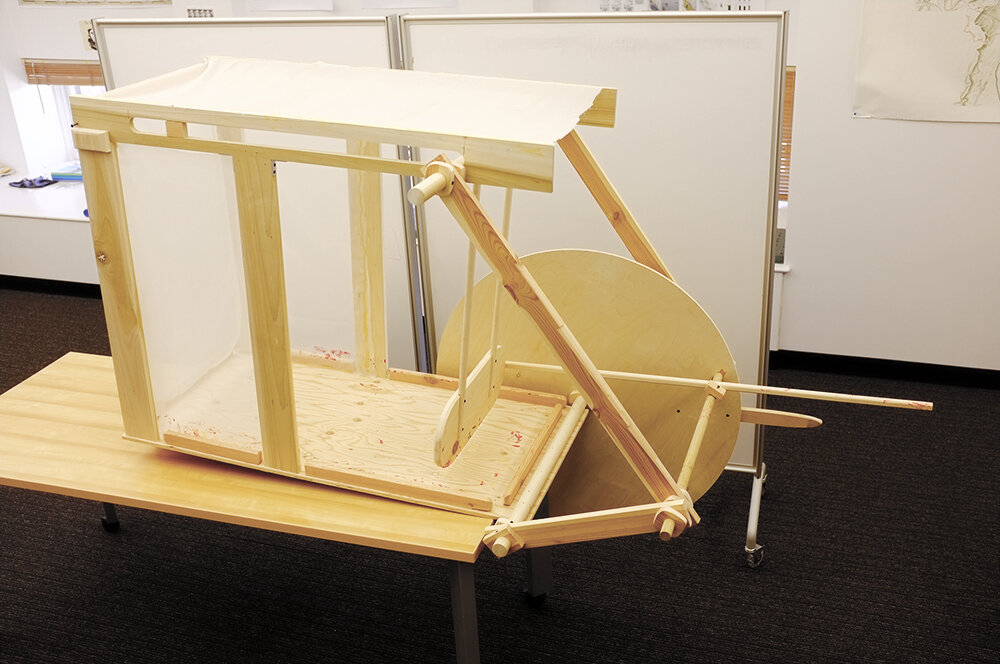

IRREPRODUCIBILITY MACHINE

The work represented on this page stems from my participation in the graduate studio course Kinetic Sculpture, taught by Professor Terry Berlier at Stanford University in 2015.

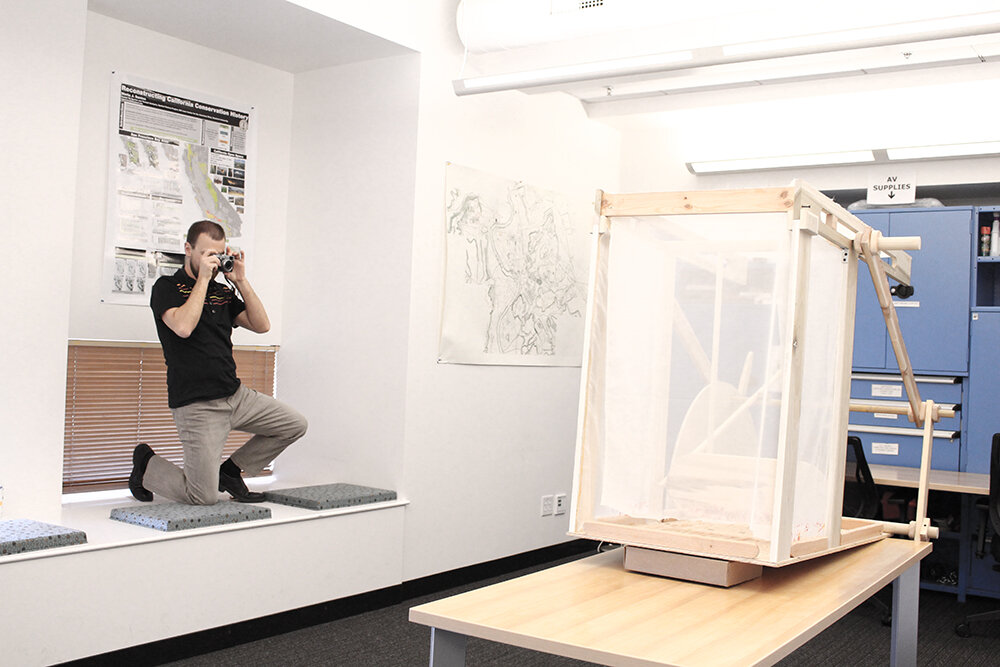

The Machine in action:

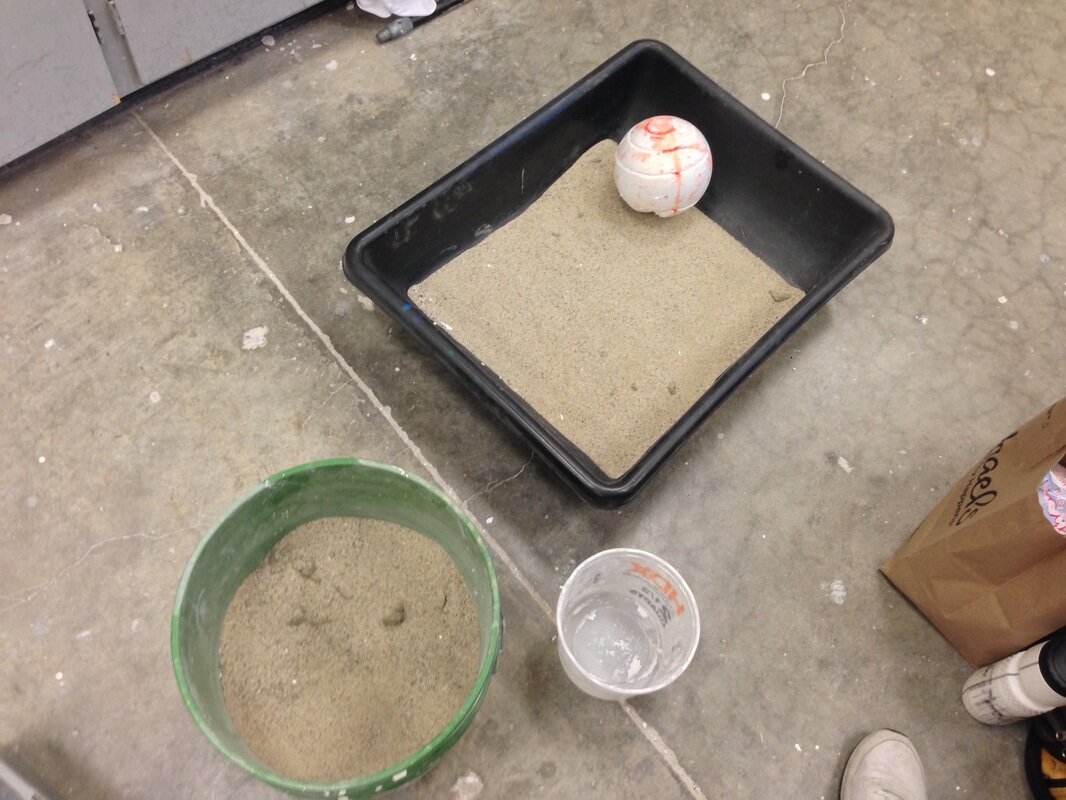

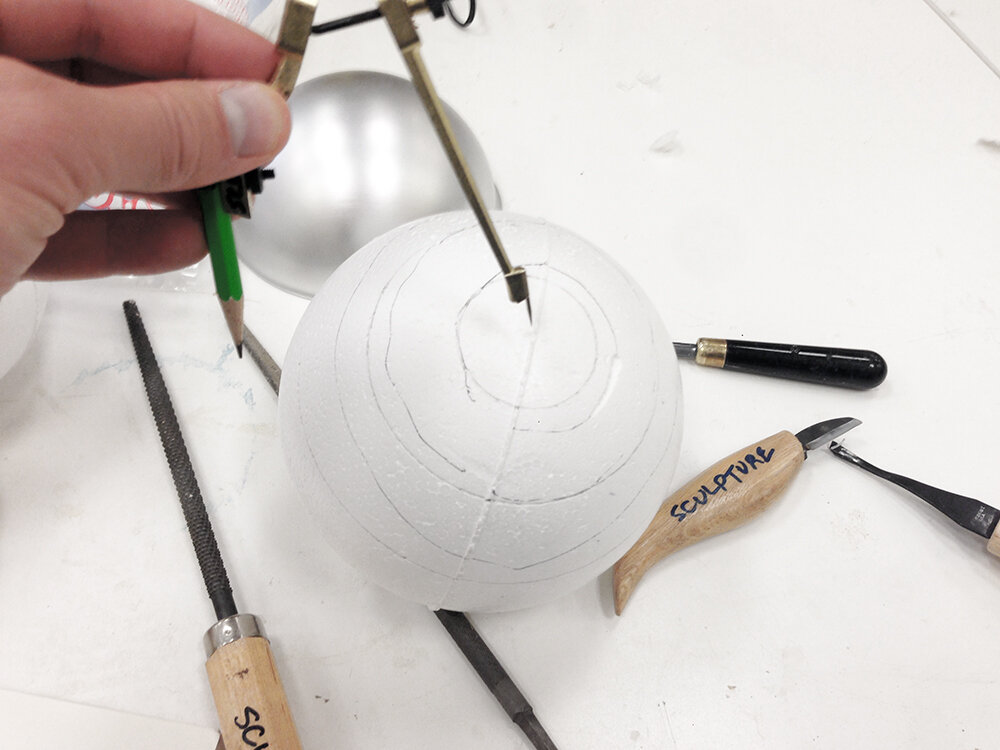

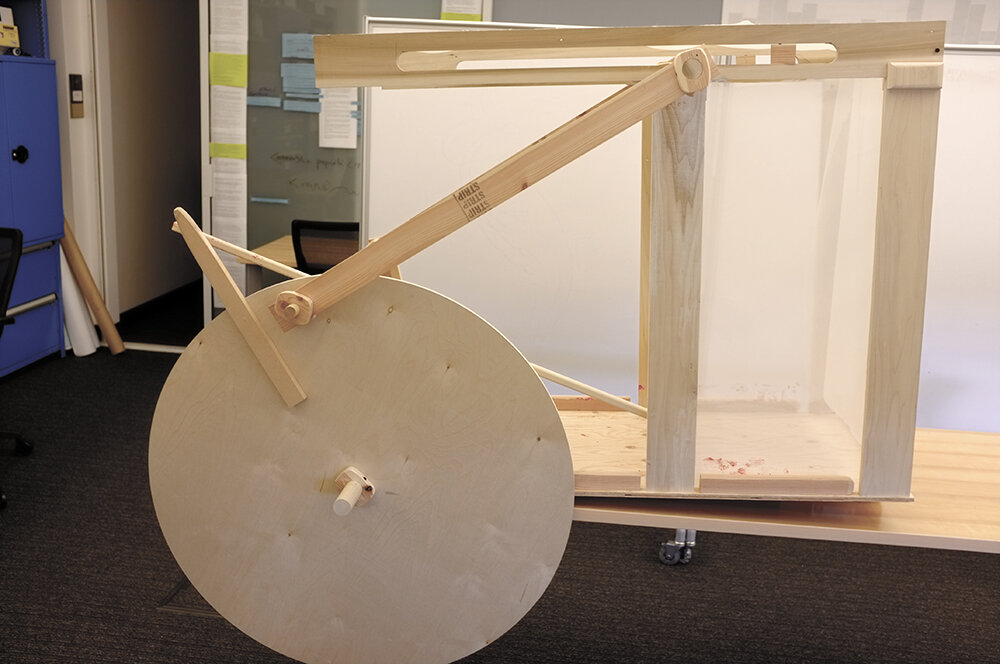

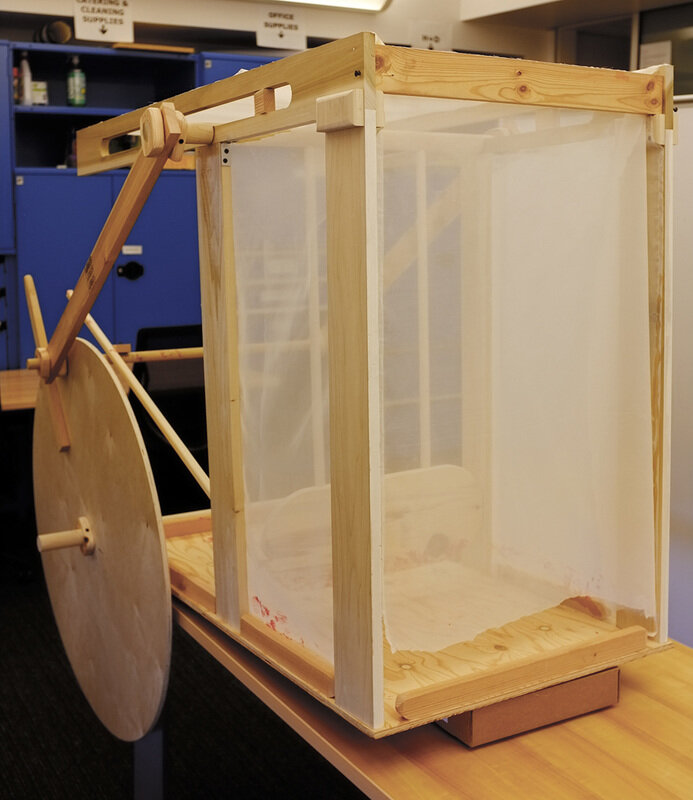

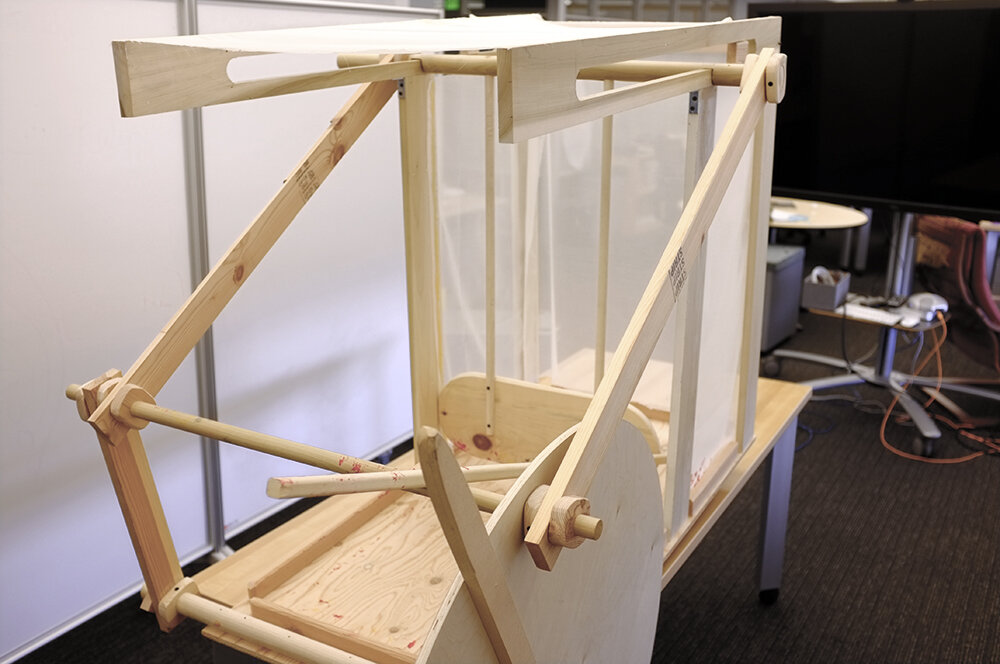

We use machines to reproduce things over and over. This mechanics of reproduction is at the heart of economies of scale, which is to say that by making an unlimited amount of a single product the very notions of artisanship and craftsmanship are threatened, relegating them to small-batch, elite consumption. So, this machine never makes the same thing twice. It's a kinetic sculpture that looks like it could really do some efficient work - could really make someone some money - but in the end forges something new each time, rendering its role in the motive of profit completely useless.

STILL IMAGES

SOME NOTES ON DOING KINETIC SCULPTURE

In sculpture, ideas are not to be logically debated, but expanded out to an imaginative, tactile conclusion. The glideslope from idea to object is steep, sometimes immediate. This is thinking with your hands.

The point is not to achieve something deeper, like a grand claim or a thesis. The end, rather, is that you took a concept and moved it into a pliable form. You actualized it. You brought the concept into a dimensional space that exceeds the mere statement or proof of the concept. You materialized it. You made it so that it could be seen from different perspectives. You struggled not with grand claims regarding its significance, but with the process of transposing thought into form. This transposition of a thought into another dimension is the pay dirt in sculpture.

It's doing, not analyzing.

It's pushing forward to see where it goes, not being cobbled by self critique.

Don't want to explain or argue.

I want the work to speak.

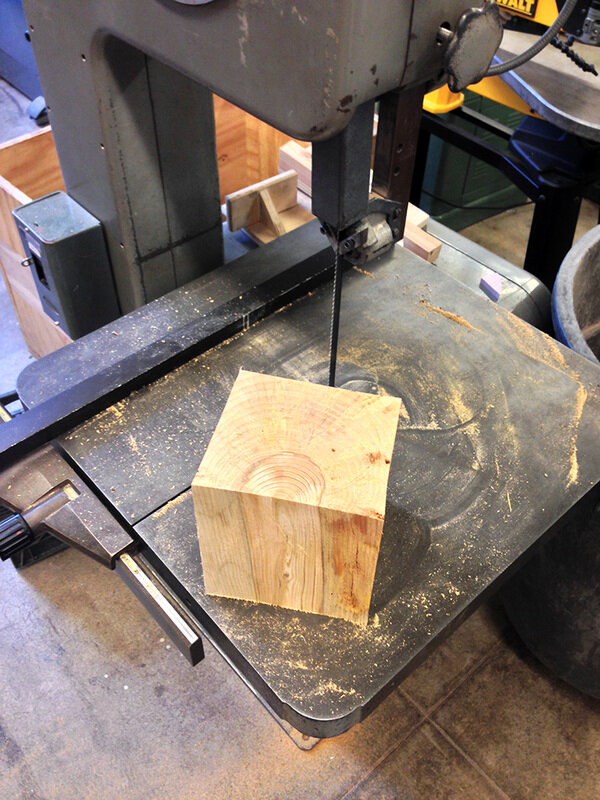

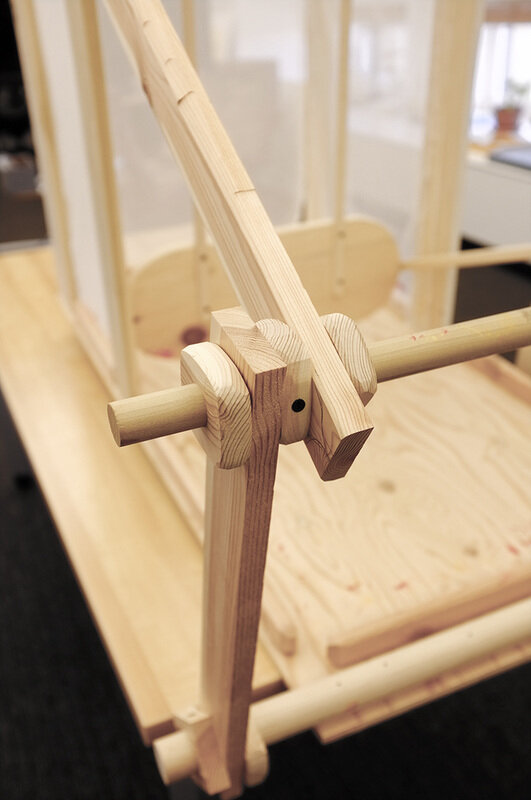

Doing sculpture brings you deep inside the details. In the world of intellect and words, each word functions as a category of meaning that is never specific. A word always connotes, and therefore words can be used to cover what is really in your mind. They allow you to ignore, uninvestigated, what your thoughts are made of. Of course with care they allow expression, too. But words elide the structures and patterns of how ideas are put together. They gloss more often than they pinpoint. Sculpture, on the other hand, leaves no room for this intellectual laziness. There is nowhere to run; it's all in the details. You can't say that a crank will turn an arm. You have to know how that will happen. What will the joints be? You have to know how the pieces are put together. There is no room for black-boxing any stage of the process. There is no "cutting a log," there is only "cutting a log with a bandsaw." This insight into process can, however, be carried back to writing. Every piece of an essay has to be conceived and executed in a way that shows fully its inner workings. There can be no fraction of a thought in one's mind unexpressed. Un-mined pieces of ideas produce sloppy, dysfunctional results, just as unmade joints result in broken objects.

I use kinetic sculpture as an analog (in both senses of the term: metaphorical, and non-digital) for creative production that is not within my normal paradigm. I use kinetic sculpture to study patterns of making and thinking from a totally different perspective. This medium allows me to abstract - to get at the nuts and bolts of how the creative process works because I am not mired down in the familiar content of cultural geography, and the old habits of writing that I've developed. I can then re-inset what I learn about making, doing, and building into my already established work flow.

The following is inspired or quoted from Theo Jansen, The Great Pretender, 2007:

"The strategy I followed to assemble the animals is in fact the complete opposite of that taken by an engineer." Engineers "have ideas and then they make these ideas happen. First they pore over books, then they open all the drawers in their workplace and take out what they need. It's a working method that gives rapid and reliable results, no two ways about it." But what they make would likely be very much the same.

"Everything we think up can in principle be thought up by someone else. Now real ideas, as evolution shows us, occur by sheer chance."

The artist's method is that "your destination has yet to be decided. You park your car along the hard shoulder and scramble down the bank, machete in hand, hacking a path through the undergrowth. You'll probably never arrive at a destination in the accepted sense of the word, but you are very likely to call in at places where no-one has ever been before."

BIBLIOGRAPHY FOR KINETIC SCULPTURE

Barber, Thomas Walter. 2013. A Victorian Handbook of Mechanical Movements. Mineloa, NY: Dover.

Berry, Ian. 2001. Chain Reaction: Rube Goldberg and contemporary art. Williamstown, Mass.: Williams College Museum of Art and the Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery.

Brett, Guy. 2000. Force Fields: Phases of the kinetic. London: Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona.

Elkins, James. 2001. Why Art Cannot Be Taught. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Fischli, Peter, and David Weiss. 1987. The Way Things Go [DVD]. Germany: T&C Film AG.

Jansen, Theo. 2007. The Great Pretender. Rotterdam: 010 Publishers.

Jenkins, Jim, and Dave Quick. 1989. Motion Motion Kinetic Art. Salt Lake City: Peregrine Smith.

Le Feuvre, Lisa, ed. 2010. Failure. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Liechti, Peter (director). 1995. Signer's Suitcase. Switzerland: Peter Liechtli Filmproduktion.

McMaster-Carr Catalog of Parts. 3,888 pages, available at www.mcmaster.com

Peppe', Rodney. 2004. Automata and Mechanical Toys: With illustrations and text by Britain's leading makers, and photographs and plans for making mechanisms. Ramsbury: Crowood Press.

Sculpture (a publication of the International Sculpture Center). May 2015; Vol. 34, No. 4.

Thornton, Sarah. 2008. Seven Days in the Art World. First ed. London: Granta.

Tinguely, Jean. 1973 [1961]. Untitled Statement. In ZERO, edited by O. Piene and H. Mack. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.